Teaching English as a Foreign Language – Food for Thought: Thinking and Teaching about Food

For various key topics in the EFL classroom, the teacher can use nutrition and food as a cross-cutting theme. Food offers many starting points for personal and individual reflection and association. It also relates to issues in the curriculum, such as food, health, leisure time, and the environment. Food and nutrition are relevant to the discussion of leisure behavior, e.g. cooking, animal husbandry, gardening, and sports. Furthermore, the discussion of several cultural practices is directly or indirectly related to food traditions, as bank holidays can exemplify (Christmas meal, Thanksgiving dinner, traditional breakfast, wedding). Social, cultural, and economic topics, which the teacher can illustrate with the help of nutrition, represent other opportunities (social differences, international food companies, globalization or food production).

Das Quellen- und Literaturverzeichnis zu dieser Seite finden Sie hier.

Aufgabe 1 von 2

The subsequent lesson should draw the pupils’ attention to certain questions and perspectives related to nutrition and raise awareness of their own habits and behavior in this respect. To refrain from using exhausted topics, the students examine excerpts from current texts. The texts are authentic and non-fictional and belong to the genre of Creative Non-Fiction. In an entertaining way and on the basis of creative text procedures, the students briefly present current facts, which are enriched by their own personal experiences.

Read the following suggestions for a lesson on the topic "Food for Thought: Thinking and Teaching about Food."

Lesson Plan

pre-reading activity: The students try to remember the ingredients of their last breakfast and then work in pairs and brainstorm on the origin of the products.

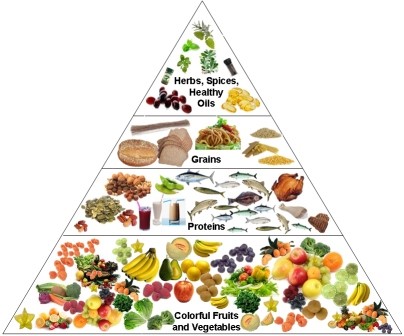

while-reading activity I: The teacher familiarizes the students with the food pyramid (figure 1) and the students learn about the food groups and their characteristics. With the help of informational texts, the students study the different diets (omnivore, vegetarian, vegan, fasting) and discuss possible reasons for these dietary choices.

while-reading activity II: The teacher hands out excerpts from two authentic creative non-fictional texts: Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life (2007) by Barbara Kingsolver and the chapter "Dining Room" in Bill Bryson's 2010 book At Home: A Short History of Private Life (worksheets 1-3). The students first read the texts, make sure that they know all the words, sum up the gist of the extracts and discuss it with the class. They familiarize themselves with the "locavorism" diet and the vitamin content in food and supplements. By working with the excerpts, they learn how to skim a text in order to identify key ideas and also how to obtain specific information, that is to say how to scan a text.

post-reading activity: In order to inform their customers about the quality and origins of the ingredients of McDonald’s products, the fast food chain started a campaign in 2014 which they named "Our Food, Your Questions." In video clips and online postings, McDonald’s replied to the questions asked by their customers. The teacher introduces the campaign to the students and asks them to come up with their own questions for McDonald’s with the help of the texts from the while-reading phase. Then the students watch the commercial for the campaign "Our Food, Your Questions" and visit the official website for the campaign launched by McDonald’s Canada. After having watched the commercial and accessed the website, the students compare their own questions with the ones in the commercial and on the website. The students then reflect on the strategy behind "Our Food, Your Questions" and evaluate the effectiveness of the campaign.

Below, you will find the relevant resources for the lesson plan.

Figure 1: Nutrition Pyramid

Worksheet 1: Food Culture

"This is the story of a year in which we made every attempt to feed ourselves animals and vegetables whose provenance we really knew. We tried to wring most of the petroleum out of our food chain, even if that meant giving up some things. Our highest shopping goal was to get our food from so close to home, we’d know the person who grew it." (Kingsolver 2007: 9-10)

"Humans don’t do everything we crave to do – that is arguably what makes us human. […] With reasonable success, we mitigate those impulses through civil codes, religious rituals, maternal warnings – the whole bag of tricks we call culture. Food cultures concentrate a population’s wisdom about the plants and animals that grow in a place and the complex ways of rendering them tasty. These are mores of survival, good health, and control of excess. Living without such a culture would seem dangerous. […] A food culture is not something that gets sold to people. It arises out of a place, a soil, a climate, a history, a temperament, a collective sense of belonging. […] People hold to their food customs because of the positives: comfort, nourishment, heavenly aromas." (Kingsolver 2007: 16-17)

"At its heart, a genuine food culture is an affinity between people and the land that feeds them." (Kingsolver 2007: 9-10)

Worksheet 2: Eat Your Greens

"I’ve grown up in a world that seems to have a pill for almost everything. […] If there’s no time to eat right, we have nutrition pills, too. Just pop some vitamins and you’re good to go, right?

Both vitamin pills and vegetables are loaded with essential nutrients, but not in the same combinations. Spinach is a good source of both vitamin C and iron. As it happens, vitamin C boosts iron absorption, allowing the body to take in more of it than if the mineral were introduced alone. When I first started studying nutrition, I became fascinated with these coincidences, realizing of course they’re not coincidences. Human bodies and their complex digestive chemistry evolved over millennia in response to all the different foods – mostly plants – they raised or gathered from the land surrounding them. They may have died young from snakebite or blunt trauma, but they did not have diet-related illnesses like heart disease and Type II diabetes that are prevalent in our society now, even in some young adults and children. Our bodies aren’t adapted to absorb big loads of nutrients all at once […], but tiny quantities of them in combinations – exactly as they occur in plants. Eating a wide variety of different plant chemicals is a very good idea […]. You don’t have to be a chemist, but color vision helps. By eating plant foods in all different colors you’ll get carotenoids to protect body tissues from cancer (yellow, orange, and red veggies); phytosterols to block cholesterol absorption and inhibit tumor growth (green and yellow plants and seeds); and phenols for age-defying antioxidants (blue and purple fruits). […]

My friends sometimes laugh at the weird food combinations that get involved in my everyday quest to squeeze more veggies into a meal, while I’m rushing to class. (Peanut butter and spinach sandwiches?) But we all are interested in staying healthy, however we can." (Kingsolver 2007: 59-60)

Worksheet 3: A Disorderly Bunch

"The realization that an inadequate diet was the cause […] of a range of common diseases was remarkably slow in coming. […] Clearly some thing or things were present in some foods and missing in others, and served as a determinant of well-being. It was the beginning of understanding of ‘deficiency disease’, as it was known." (Bryson 2010: 245)

"The vitamins are, in short, a disorderly bunch. It is almost impossible to define them in a way that comfortably embraces them all. A standard textbook definition is that a vitamin is ‘an organic molecule not made in the human body which is required in small amounts to sustain normal metabolism’, but in fact Vitamin K is made in the body, by bacteria in the gut. Vitamin D, one of the most vital substances of all, is actually a hormone, and most of it comes to us not through diet but through the magical action of sunlight on skin. Vitamins are a curious thing. It is odd, to begin with, that we cannot produce them ourselves when we are so very dependent on them for our well-being. If a potato can produce Vitamin C, why can’t we? Within the animal kingdom only humans and guinea pigs are unable to synthesize Vitamin C in their own bodies. Why us and guinea pigs? No point asking. Nobody knows. The other remarkable thing about vitamins is the striking disproportion between dosage and effect. Put simply, we need vitamins a lot, but we don’t need a lot of them. Three ounces of Vitamin A, lightly but evenly distributed, will keep you purring for a lifetime. Your B1 requirement is even less – just one ounce spread over seventy or eighty years. But just try doing without those energizing specks and see how long it is before you start to fall to pieces." (Bryson 2010: 247)